The Enclave and the Open

Rituals of Exit

There's an old saying: Noah's Ark was a noisy, smelly place to be, but it was better than being outside. This is supposed to be a metaphor for the Church. There are some things that might be said about it, but for now I'm only interested in how this particular image of redemption imagines space.

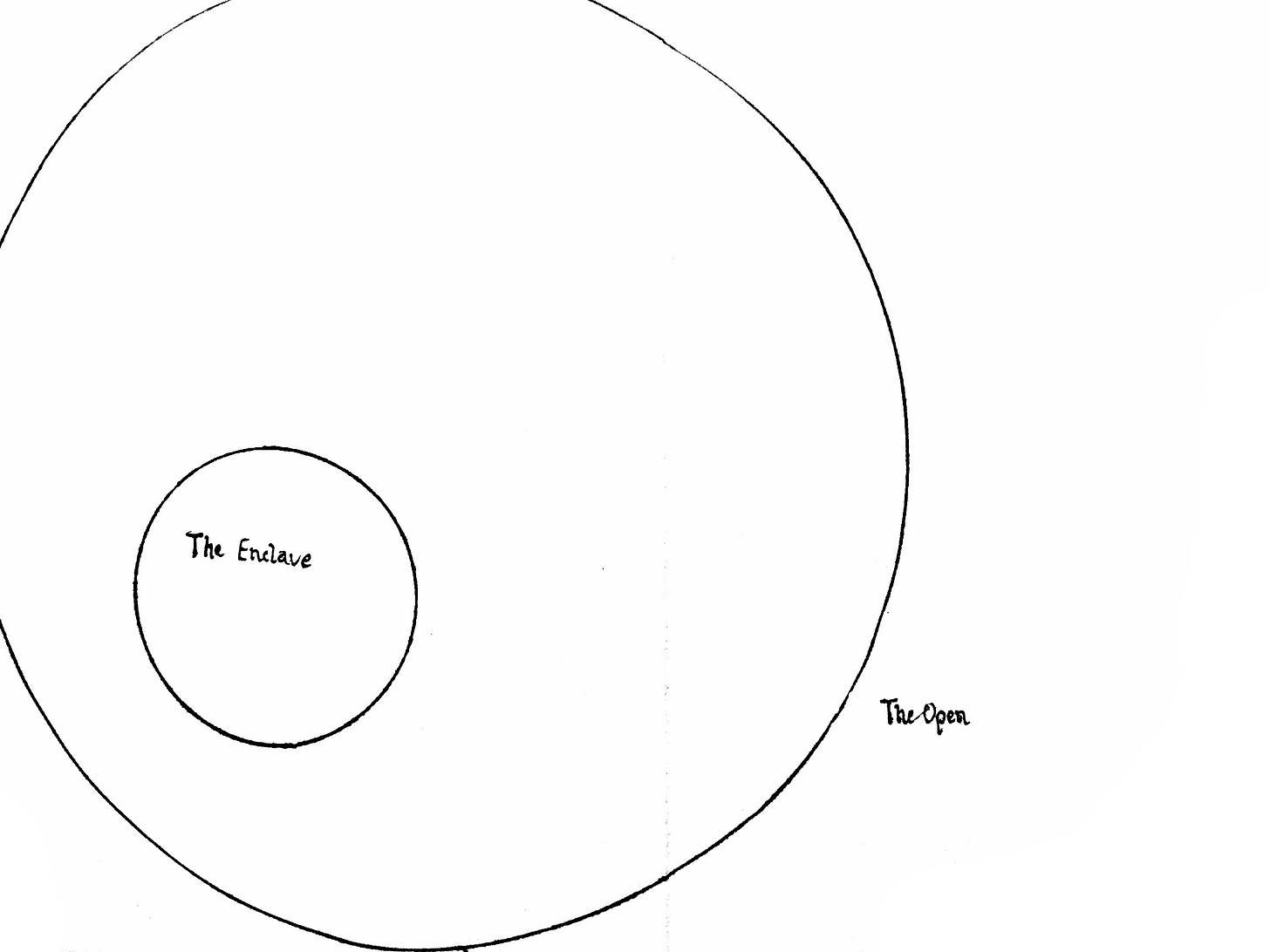

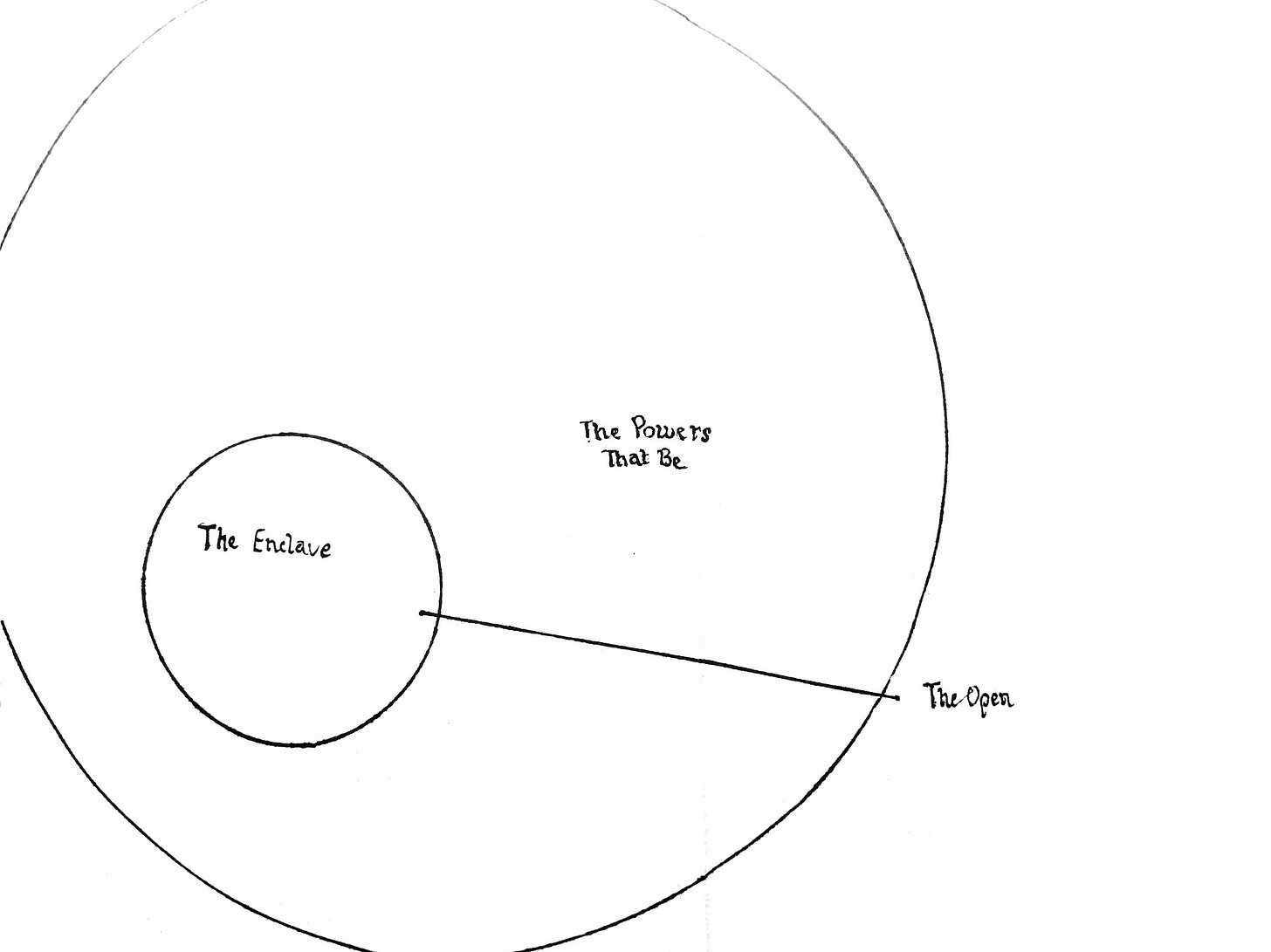

In the religious communities I have known, salvation tends to be described as an entrance into some safe place. The chaos of the world remains outside. One is baptised into the Church, or into Christ, or into Christianity. One is saved into the fold. Marginalised groups campaign to be in-cluded. People accused of heretical shenanigans might be ex-communicated, which of course means to be cast out. In other words, salvation is described by metaphors of entrance. “I am the gate,” says John's Messiah. And so on.

How else would anyone imagine such things? Well, some have used the opposite metaphor, where redemption is described as a liberation out of something rather than entry into something. It’s an exit, or an exodus even. The ex might not be the worst prefix afterall.

This is not a question of either/or. And yet, these spacial metaphors are not simply interchangeable either. They communicate very different things about what is happening. They feel different. They carry different virtues and are open to different dangers and vices.

Metaphors of salvation by entrance point to images of embattled communities: the bunker, the fortress and the secret society. They're about resistance and resilience, militancy perhaps, purity, defiance and peculiarity. They cast the world in the image of violence or chaos or wickedness. Whoever makes it onto the ark is obliged to live contrary to an outside world from which they cannot fully remove themselves. Wartime resistance movements, revolutionary groups, cults, nation states, mafias, religious communions. There are some very different ways of wearing this story. Its virtue is to be found in its way of seeking out some ground to live out alternative possibilities within a prevailing and unfavourable situation. Its possible vices lurk in the felt need to control the community and keep it pure, in its over-simplification of the world beyond itself, its tendency toward an embattled and enclosed sort of energy, and its difficulty in imagining itself apart from in opposition to its enemies, who become vital to its identity.

Meanwhile, metaphors of exit evoke images of mass migration into some wild open. They’re found in the calm of the outward breath, as though the imperial walls were already ruins in the dust behind. In an exodus metaphor the earth is an abundant open that stretches far beyond the realms of control and oppression: it is the space of enclosure that ails the world. These energies lean toward apocalyptic and utopian sensibilities. They are sometimes reckless and idealistic. Unlike metaphors of entrance, exit narratives lean away from law and control. They hazard the risks, the dangers and the madness that grow close to the tree of liberation. They exist in a sort of tension with the unresolved and unliberated realities of life on the ground.

These two metaphors are always both in play in any one movement, though the ratios will vary. It's never a matter of one or the other. It's about the balance and the dialogue between the two. I want to tell a neglected side of the story so I'll risk the appearance of favouring one against the other; of preferring the open to the enclave (though, who would not prefer it, in the end?). However, it is possible to overshoot the necessary madness of hope and be left with just madness, so I will say from the start that savvy always talks in both directions.

Many of the religious worlds I’ve known have self-described as enclaves of salvation from the world: a place one might enter into. I always found this description somewhat at odds with my childhood practice of prayer; my habit of talking and listening and humming tunes and drones with God. I experienced this relationship as a boundless open which transfigured the world into a realm of awe, beyond control or ownership. In that realm the earth was somehow relaxed, under all the surface noise of the grown up world. Having said that, I was not closed to the secretive, conspiratorial pamphleteering spirit that was also part of those worlds. If there was a tension, it was not a conflict as such.

The prevailing language of the enclave—the ark of salvation—often came to me in the guise of exceptionalism and quietism. This religion was better than the world, but the world was doomed to always be as it was, and so the aim was to be found among the chosen ones who would be saved. The older I get, the more I've come to view this as a sensible lack of idealism, and yet I've never been able to embrace its indifference to so many things. My prayers still lead me to the open. I can’t not feel it. I’ve never stopped finding God outside the city.

More still, I would have to read the sacred texts of my tradition with my eyes closed to not see tales of exit and liberation everywhere. “Come out of her, O my people!” so it says. Both metaphors are always in play, certainly. But while my formation was steeped in metaphors of entry, the messianic texts are, by virtue of their very messianism, more inclined toward stories of exit.

Even John's Messiah, who calls himself “The Gate”, will not be collapsed into an image of enclosure. He is—so it continues—the way by which the sheep “come in and go out.” And in the end, “when he has brought out all of his own, he goes out ahead of them.” So much outering.

The Messianic Movement of the First Century formed itself around two rituals, which they held dear. One was baptism, and the other was the breaking of bread. Both these rituals are commonly understood as points of entry: baptism as a rite of initiation into the community and the eucharist (the breaking of bread) as the ongoing rite of inclusion and membership. In the thoughts that follow here over the next months, I want to describe these rituals in the opposite terms; not as modes of entry but as rituals of exit.

Barry Lopez's book of interlinked stories, Resistance, is all about this kind of exit...

Thanks David for this message and I am looking forward to you developing this theme. I always see religious enclaves as a sort of time bubble! The stronger the walls the more locked into a static moment in time they become. Everyone in that community wears similar clothing, the same hats, hair styles then its ideas, culture and language!

Time slows down!