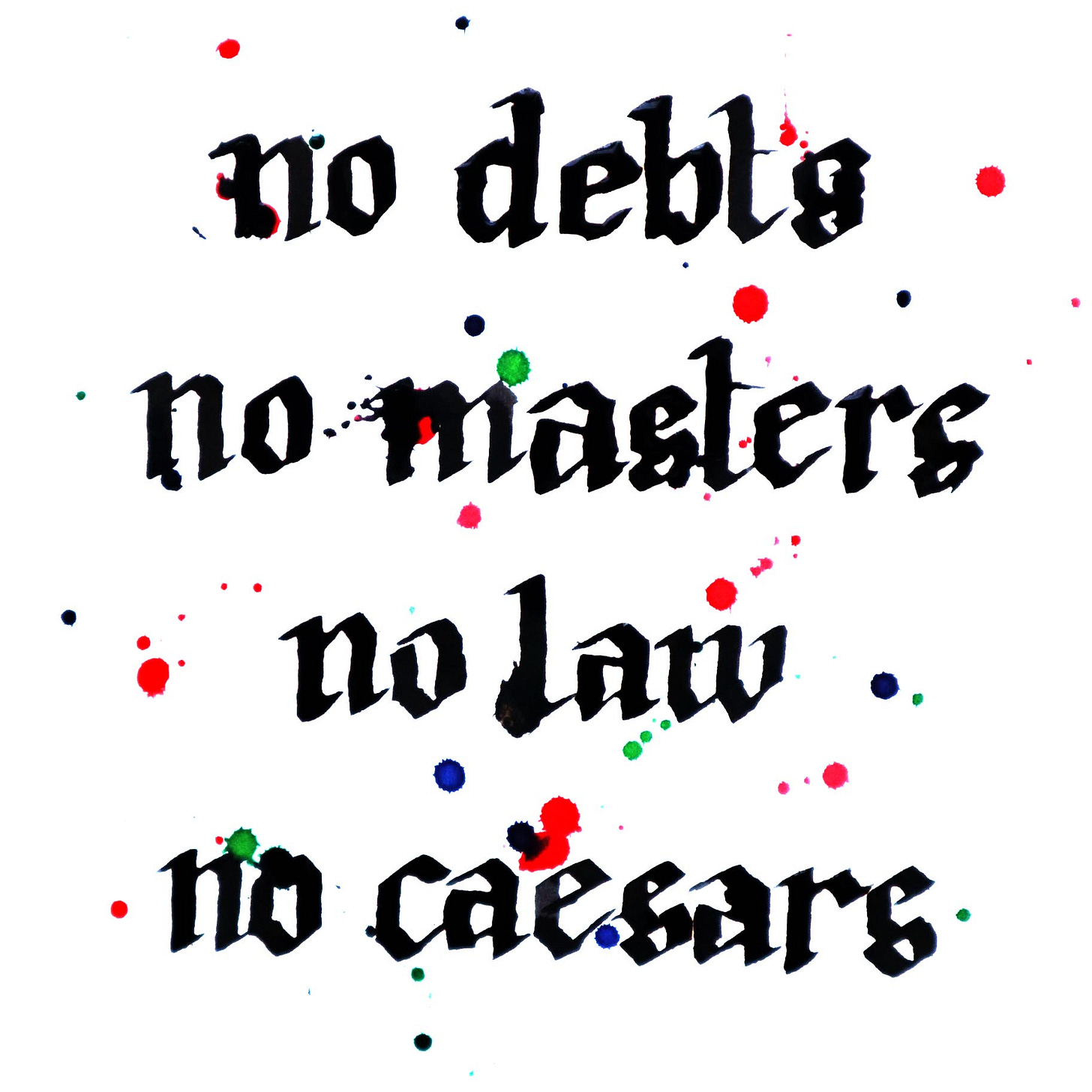

After the release of Kindness is Solid Stone last year, I had a mind to write a series of short essays relating to a chant on that record: ‘no debts, no masters, no law, no caesars…’ These four refusals seemed to converge into a sort of messianic manifesto, in my mind at least. So I set to writing about them in late December to early January.

As it should happen, I have since found myself unexpectedly landed with a handsome debt. I'm aware that some involved might keep half an eye on what I write about here, so naturally I've felt a little awkward about proceeding with these essays. I wouldn’t wish my debtors to think this has been hastily and angrily penned in response to them. To be clear, all of this, as far as the ‘debt’ section goes anyway, was written before that happening, which I (perhaps naively) had not anticipated.

I decided that it wouldn't do to hold back for fear of causing bother and I’ll trust no one will think this song is about them. Afterall, like most people, I've lived most of my adult life in systems of debt, one way or another. The timing of this one was a strange coincidence.

These short essays on these four refusals are not here drawn up to simply rail against four things we don't like (the presumptuous ‘we' that is so common these days…). The intention here is to explore how messianic visions of the past saw these four things as being totally incongruous and indeed impossible under messianic conditions. The future myth of the age to come reached toward a time after these had been totally dismantled. Why? Because none of these things can exist alongside what they called, in Greek, pistis: relationships good enough to trust.

The messianic political imagination was therefore ever inclined to refuse and subvert these four ogres, wherever it seemed possible to do so. These are tales of their successes and failures, as they tried to attune themselves to a more beautiful and creaturely kind of life together beyond the iron law of the present. These are tales in which to plant our own tales, our own successes and failures toward other ways of living.

Prayer is a Trap

My family were the kind of protestants who had no special attachment to any denomination or tradition. There was my mother's charism at one end and my father's northern fondness for the good sense of John Wesley at the other. Anything could happen in between. I spent much of my childhood as part of a Methodist church. It was faintly liturgical and every Sunday we would chant the Lord's Prayer together. It was the old language: Our father, who art in heaven… a contrite mumble of voices in the arching wooden hall. I can immediately recall the sound of the many whispered esses on the line, forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us, filling the air with sibilance.

It seemed an odd choice of words to me. As though I were a poor boy stealing apples from the landed class. I couldn't imagine being important enough to have to forgive someone who'd trespassed against me. I understood that when the room said “trespasses” it was taken to mean our personal moral failures, but it was a linguistic turn that made sinners of the poor and victims of the rich.

In Matthew's gospel, the Greek word is neither trespasses, nor sins, but debts. The cadence runs, “forgive us our debts as we forgive those indebted to us.” This is so in almost any English translation. I learned from Richard Beck that the use of “trespasses” is an archaic hangover from the Book of Common Prayer of 1549, long before the first “official” English bible of 1611. After just two generations of liturgical chanting, that word has remained rooted for four hundred years since.

As it turns out, the differences between these two words are significant. The world was not suffering because those without property were straying onto what was rightfully owned by the powerful. The issue at stake here was debt, and the prayer calls for the debts to be canceled.

Jesus is playful. He knows, I'm sure, that he has set a trap for the rich in this peasant's folk liturgy. “Pray this, if you can,” he says. First pray for enough, for daily bread, and then pray for the cancellation of your debts, because debt is the miserable end of a power relation. These are the concerns of precarious people living hand-to-mouth. But we then follow the rosary of words into a condition: “...as we forgive those indebted to us.” This prayer might be a little more difficult for the rich creditors than for the poor. It's a liturgy that subverts the one who prays it into relinquishing the economic power they wield over others. The problem with the world, in this prayer, is not the trespasses of the poor against the landed rich, but the economic power of the rich which keeps the poor in thraldom.

It is sometimes said that Jesus was not interested in politics or economics (though no one who reads any theology would say this). Some will prefer to say that none of this is really about property or wealth, and that all these words are just metaphors for personal moral failings. Certainly, in Jewish religious law, it was a personal moral failing to keep a person in debt indefinitely, to make wealth off of their struggles by charging interest, or to keep property in perpetuity. And how does a person end up indebted? Maybe through personal failings, certainly. Or maybe through life's slings and arrows, or injustices, or matters beyond their own control. In any case, this is not not about personal conduct. In the ancient Jewish moral imagination, questions of personal conduct didn’t turn a blind eye to social and economic power relations, as more fragmented worldviews have tended to do. Everything touches everything. Everything matters.

But of course, no one likes to be tricked, and no one who is carried on the shoulders of the indebted wants to free them of their obligations, just as Pharaoh prefers not to let the people go. A daily prayer calling for the cancellation of debts needs to be wrapped in a little wool before we pass it around.

Thanks David. This short essay sparked a series of small fires in my memory fields. My parents were not church goers so I rarely attended church as a child but I do recall the recitation of the Lord's prayer in school assemblies. I too remember being confused by the use of the word "trespass" and wondering what it was all about. And, yes, I also was seduced by the sibilant sound of the hall full of mummering voices. As I listened to your audio it conjured visions of satanic snakes slithering towards an apple tree in the garden. It also struck me as no coincidence that the change in translation from "debt" to "trespass" happened at the time when the enclosure of the commons began in earnest in England. Lots to ponder upon. I look forward to reading the other essays in the series.

"Everything touches everything. Everything matters." Good to read you again. Thanks for proceeding in your intended sharing. As usual, so much to open the seeking mind and longing heart. "These are tales in which to plant our own tales ... toward other ways of living." That's the call I hear, and crave to reciprocate.